In Part 1 of this series I explained why the future of education policy can’t be all about schools. Unfortunately, what I’m less sure about is what that insight might mean in practice. What I can do though, is set out some options for what it could look like. For now, I think there are three main ways an enhanced role for ‘non-school’ actors could pan out.

1. Providing

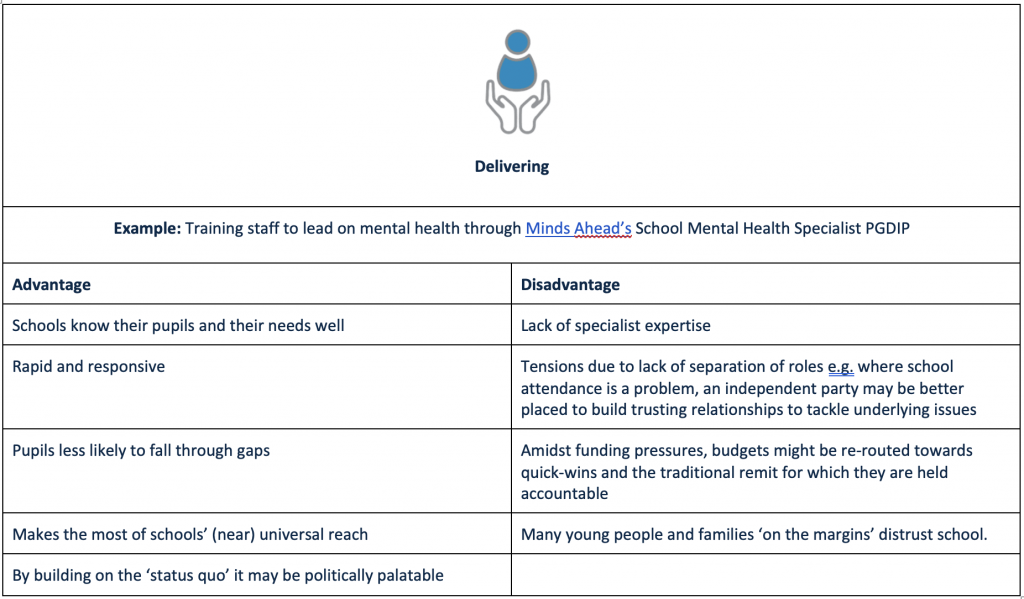

The first route means accepting, embracing, and – importantly, resourcing what is increasingly the status quo. It means recognising that educational outcomes depend on delivering far more than just teaching and learning – but then backing schools to do so.

For some teachers and schools, it is not the expanded role that they have had to take on recently that they resent; it’s the fact that austerity has forced them to become the “provider of last resort” (as Sam Freedman puts it) without the required resources. Schools might therefore be willing to step up to the plate if they were backed to do so. I recently heard one English teacher arguing for exactly this, saying “if you just give us the resources, we can sort it out”.

To some extent this is nothing new. Schools have long held pastoral as well as academic responsibilities. By organising clubs, providing food at lunchtime (and increasingly at breakfast), they are already delivering in this space, but by recruiting and training Mental Health Leads, buying washing machines to clean pupils’ uniforms and stepping into negotiations with housing services , they have dramatically increased their remit in recent years. Calls to go further abound: just last week, Public First and it’s Coalition for Youth Mental Health in Schools called on the government to invest £11.6 million a year from 2023 “into a new ITT route to ensure every secondary school in England has a specialist trained PSHE teacher by 2030”.

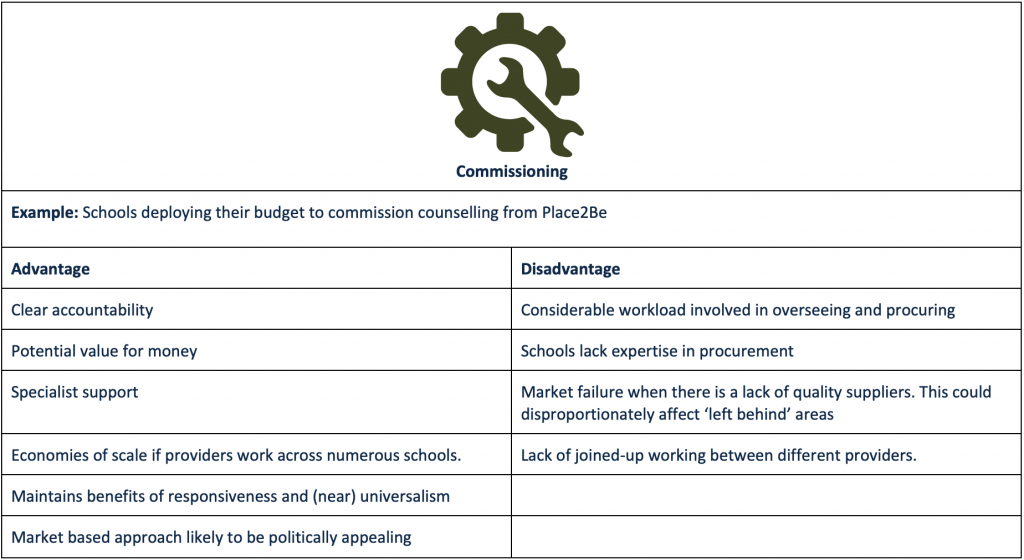

2. Commissioning

This alternative is an adapted version of the first option where schools again receive additional funding to embrace an enhanced remit – but without ‘doing the doing. Instead, they act as a commissioner or hub. This is something we see in many schools, for example where they commission mental health and wellbeing support from organisations like ‘Place2Be.’

This approach maintains some of the benefits of the first model in terms of (near) universalism and responsiveness, but brings potential additional benefits: for example allowing schools to tap into specialist expertise. Market enthusiasts might also argue that the commissioning process provides accountability and maximises value for money.

On the other hand, schools aren’t experts in procurement and unless funding is ring-fenced, there’s once again, no guarantee schools won’t spend money in areas more directly linked to short-term gains in the league tables – particularly when money is tight. Overseeing an expanded remit and managing different providers also involves huge workload at a time when this needs to be cut rather than added to. We also shouldn’t forget that some of the most marginalised pupils are not necessarily in school.

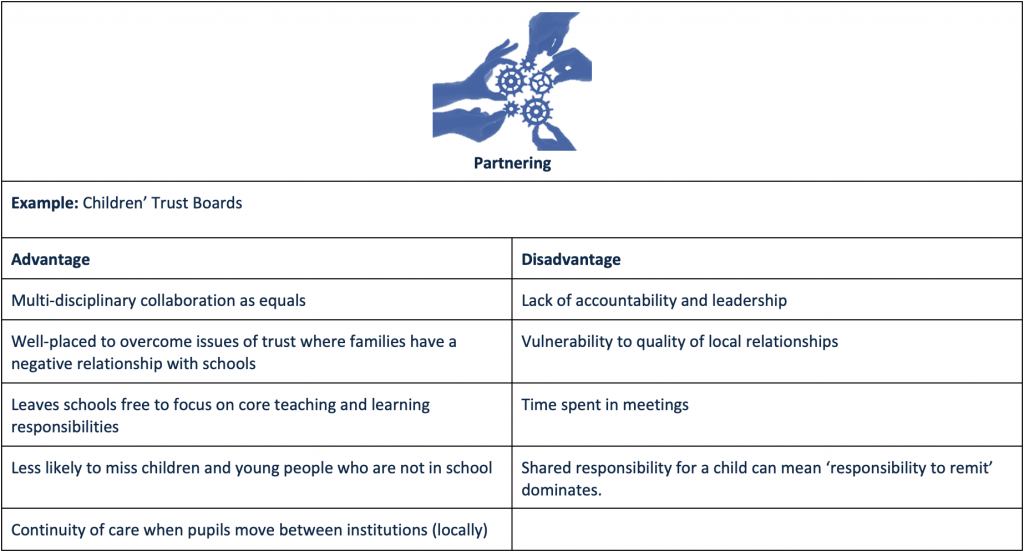

3. Partnering

Given the potential risks with both of the above options, perhaps we should be focusing more on partnership. This could look more like the traditional Local Authority model or the Children’s Trust Boards that oversee how children are doing across an area. However new approaches are also being developed: Dixon’s Academy Trust and The Reach Foundation are working with Frontline Social Work and UK Youth on a programme called “Joined Up.” Through this initiative, participants from different disciplines are working with a community to develop a new approach to supporting families. Meanwhile Leora Cruddas and the Confederation of School Trusts have argued for the role of school trusts as anchor institutions that can “use their capability and capacity to act with other civic partners”. Alternatively, Citizens UK have long argued for the role of community organisers as a means of driving change through local grassroots leadership.

The big advantage of partnership-focused models is that they need not be school-centric. Schools should not necessarily be the dominant, senior partner – despite this being the unspoken assumption in most policy discourse. Not only might this provide a better starting point for collaboration, it might also open doors with children and families who are distrustful of schools.

On the other hand, this model is hugely dependent on the quality of relationships between partners. Leadership and accountability might also be weak, leaving young people to fall through the gaps. A recurring theme in “Young People on The Margins” is that when everyone has a different remit, no-one focuses on the young person. Collaborative partnerships could also result in a lot of time lost in meetings – an argument made compellingly by Laura Mcinerney in “We need a Cross Sector Recovery Strategy” – the first episode of the excellent “Are You Convinced” podcast series which explores this and many related questions.

Conclusion

The archetypes I’ve presented here are inevitably simplistic. However I hope this typology provides some useful straw-men that encourage debate on how best to act on the evident fact that educational achievement does not depend solely on schools.

For now, I genuinely don’t know which of the three models is best. Inevitably, the answer will be ‘some combination of the three’, but we really need to know what that combination is, if we are going to tackle the very real barriers that stand in the way of all pupils achieving their potential.